Improper Payments Down from Covid-Era Highs But “Confirmed Fraud” Info Missing Amid National Scandal

In the first year of President Donald Trump’s second term, his administration was responsible for spending $24 billion more on improper payments than President Joe Biden’s administration spent his last year in office.

An improper payment is “made by the government to the wrong person, in the wrong amount, or for the wrong reason,” according to federal guidelines. These administrative errors include both overpayments and underpayments made because of missing or incorrect information.

The federal government made $186 billion worth of improper payments FY25, Trump’s first year back, versus $161 billion in FY24, Biden’s final year.

However, historical context is key.

That final year in office for Biden saw surprisingly low improper payments, in part because massive Covid-related improper payments began to taper off.

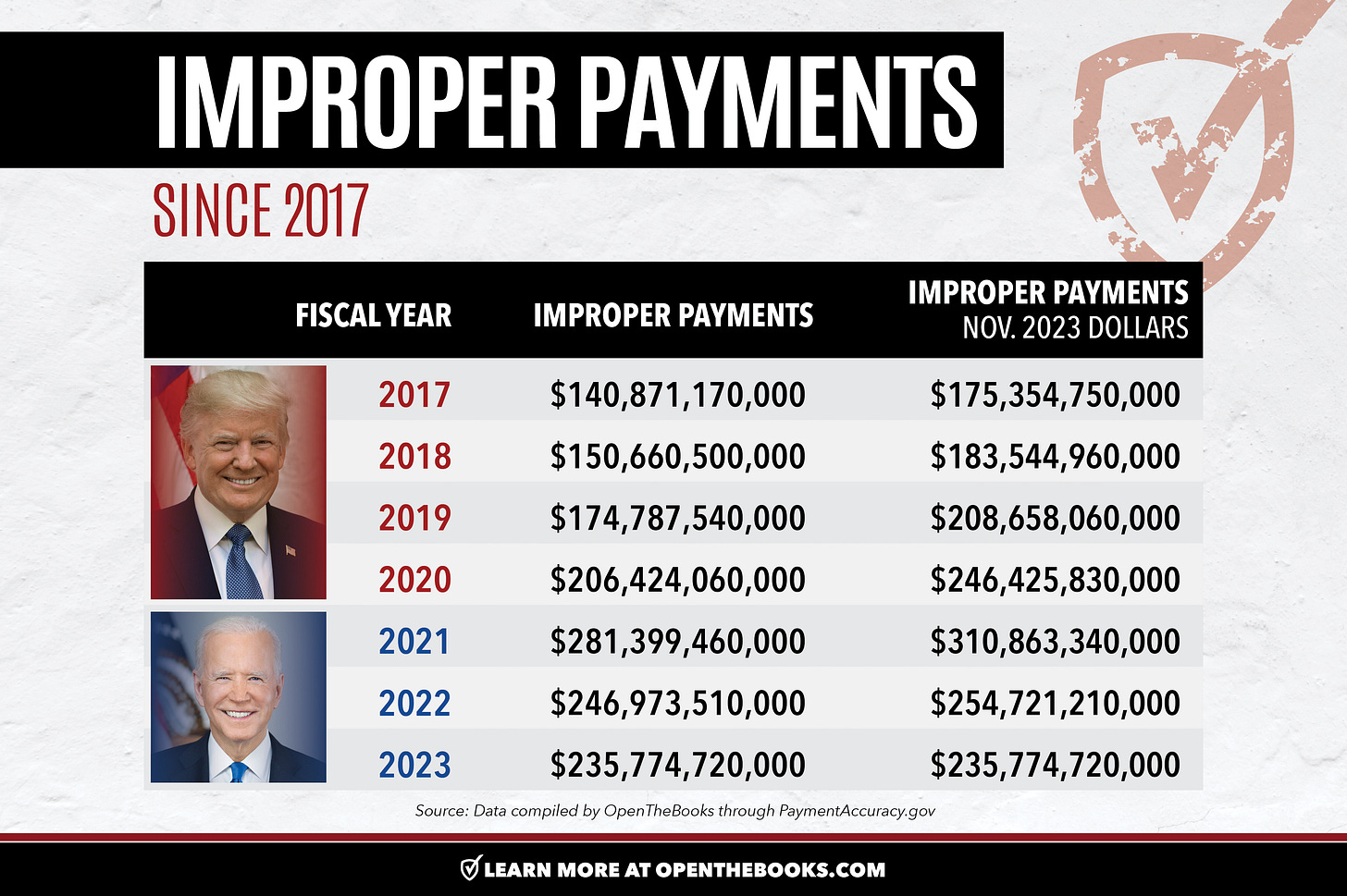

The first three years of the Biden Administration saw between $236 billion and $281 billion in improper payments annually.

Even Trump’s final year of his first term, FY 2020, had over $206 billion in improper payments.

Last year’s $186 billion is lower than each of the four years prior to FY 2024.

Trump’s first term saw between $141B and $206B — for a $168B average (not adjusted for inflation) or between $175B and $246B — for a $203.5B average when adjusted for inflation.

While improper payments have receded from historic highs of the Covid era, major transparency problems remain. Amid a series of fraud-related scandals in the news, the FY25 report fails to include the usual section tabulating “confirmed fraud.”

Improper Payments Year over Year

The Office of Management and Budget develops guidance for agencies to estimate, report, and correct improper payments. The Government Accountability Office audits agency compliance, and the Treasury Department maintains a “Do Not Pay” list to prevent improper payments before they occur.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has historically been the big loser of federal funds when it comes to improper payments.

Improper payments at CMS make up more than half of all improper payments each year. That’s $96.1 billion of the $186 billion in FY25. Similarly, in FY24, $87 billion of the $161 in improper payments were attributed to CMS.

The misappropriation of CMS funds should come as little surprise. CMS Administrator Mehmet Oz has said there is “another big crisis” concerning alleged social services fraud in Maine, which may be on par with the welfare fraud scandal in Minnesota.

Republican lawmakers in Maine brought the issue to light following December allegations from a whistleblower that the state’s Medicaid program had been defrauded of millions of dollars.

Lack of Compliance, Transparency

Some of these payments do get recovered: almost $24 billion (13%) of federal overpayments from last fiscal year have been recouped by the feds.

But there are likely more financial errors that have not been accounted for, in part because not all agencies report improper payments.

The Payment Integrity Information Act of 2019 (PIIA) (P.L. 116-117) and Appendix C to Circular No. A-123, Requirements for Payment Integrity Improvement require all federal agencies to report improper payments.

An agency can be considered noncompliant for a number of reasons. They could fail to report their improper payments, only issue partial reports, have error rates that are unacceptably high (above 10%), or have insufficient risk management programs in place. Some agencies are chronically noncompliant while others seesaw back and forth over the years.

The most recent report lists 63 agencies that have been reviewed for compliance since 2011.

FY24 is the last year available in the FY25 report, as it states the FY25 compliance status “will be updated in [the] 2026 dataset.”

Forty-eight agencies were compliant and 15 were not, making for a 76% compliance rate. Agencies can report some improper payments while failing to report others and thus be labeled noncompliant.

Most agencies that were noncompliant in FY24 have long histories of it.

The 15 noncompliant agencies in FY24 include several major Cabinet agencies and one of the biggest budget items, the Pentagon. The Department of Treasury itself is noncompliant due to having multiple programs with high error rates. Other agencies on the most recent list include Departments of Labor, Health & Human Services, Housand and Urban Development, Agriculture and Veterans Affairs.

HHS, Treasury, USDA and VA have been noncompliant each of the last 14 years; SBA, DOL and DOD/DOW have been noncompliant 13 of the last 14 years; DHS, SSA and HUD have been noncompliant 12 of the last 14 years.

Although the State Department hasn’t reported its improper payments since FY 2008, it has been deemed compliant since FY 2012.

Sophisticated Fraud Schemes

Beyond the payments “made by the government to the wrong person, in the wrong amount, or for the wrong reason,” the GAO stated in 2024 that it also believes there are undetected, “sophisticated fraud schemes” not included in the annual improper payment estimates.

“Confirmed fraud” is a dataset that is usually included in the improper payments report but is excluded in the FY25 report.

While the FY24 report contained 11 sets of data, the FY25 report only has six.

Missing data tabs are:

Improper payment totals from previous years

Monetary loss root causes: this section explains whether overpayments were inside or outside the agency’s control, whether the information needed exists, or if the agency failed or was unable to access the information needed.

Eligibility amount: these are payments that don’t match a recipient’s eligibility, i.e. address/location used by DOD for civilian pay or travel pay or age for Social Security

Confirmed fraud: this explains which programs in each year had fraud confirmed by a court and how much (FY24 was over $7 billion)

Recovery details: while the tab for “rate and amount of recovery” is present, missing are more details about the recoveries, like whether an audit was involved or the inspector general investigated (FY24 was $22.6 billion or 14%)

Arguably the most important of these is “confirmed fraud.” There was over $7 billion confirmed in FY24 but we don’t know how much was confirmed in FY25. We also don’t know which agencies and programs have fared worse or better.

Amid the fraud-related scandals in Minnesota, Maine and beyond (all of which involve federal tax dollars), this piece of reporting is more newsworthy and relevant to taxpayers than ever. But now it’s become another blind spot for taxpayers.

The worst agencies and programs for confirmed fraud in FY24 include HHS ($2.8 billion) and DOD/DOW ($2.4 billion)

Agencies with a history of noncompliance also, unfortunately, have a history of confirmed fraud.

For instance, HHS has been noncompliant each of the last 14 years, while the agency lost $28.5 billion to confirmed fraud in the time period between 2017 and 2024.

Both DOD/DOW and DOL have been noncompliant 13 of the last 14 years. The Pentagon lost $10.8 billion to confirmed fraud in that time period between 2017 and 2024 and DOL lost $5.6 billion.

USDA and VA have been noncompliant each the last 14 years. VA lost $1.3 billion to confirmed fraud between 2017 and 2024, while USDA lost over $1 billion to confirmed fraud.

DHS has been noncompliant 12 of the last 14 years, and lost $181.6 million to confirmed fraud in that same time period.

We asked the agencies responsible for setting guidelines, measuring compliance and issuing reports (OMB, GAO and Treasury) why the data is missing and have not received a response.

Incremental Improvements

While there are still glaring holes in the improper payment data and huge losses for taxpayers, one recurring problem was recently addressed by Congress. After bipartisan support in both chambers, President Trump signed the Ending Improper Payments for Deceased People Act into law in early February.

A significant source of improper payments have been checks being cut to dead people. Open the Books found $3.6 billion worth of stimulus checks sent to the dead as part of its investigation into Covid-related waste and fraud. The Internal Revenue Service had not used data from the Social Security Administration’s list of deceased persons. Simple knowledge sharing would have fix the problem.

The new law finalizes a temporary arrangement allowing Social Security to share its data with the Department of Treasury, which keeps a master “Do Not Pay” list. Now agencies using the master list can avoid payments to the deceased.

Click here to download the full dataset for FY25.

FURTHER READING

Final Tally for Biden-Era Improper Payments? $925 BILLION (Open the Books, Substack, 12 Feb 2025)

But no one is auditing these agencies to find out where their budgets are actually being spent.. Solari.com is up to $55 Trillion in actual theft from federal treasuries. When is Open the Books going to start discussing why we are not allowed to audit federal agencies: FASAB Ruling 56.

When is Open the Books going to start calling for the dissolution of unelected and unaccountable organziations that somehow create binding regulations that undermine and destroy our Constitutional right to " Government BY the People."

More and more I see OTB as a limited hangout, herding us to a spot analytically and informationally. Has anyone at OTB ever taken a look at the stuatory basis for money control regulations within the government. Check out PTAR - The Parallel Table of Authorizations and Rules. Under the PTAR, the IRS is using two statutes as it's basis for it's primary actions against citizens - when neither of those statutes was written to be used in that fashion.

All you do is publish the wow info. What about the structural and procedural rot that makes it happen?

They act as though the money is water running through their fingers. Why can't they claw much of the misdirected or improper payments back? From everyone that received them?