DOGE’s Unfinished Business

Our Review of DOGE’s Work Shows It's Up to Congress to Enact Savings

Elon Musk has officially stepped back from his day-to-day engagement with DOGE, but he took time last week to offer a useful reality check about DOGE’s progress and the challenges ahead. While speaking to the Qatar Economic Forum, he made his office’s limitations clear to Bloomberg reporter Mishal Husain: “DOGE is an advisory group; we are doing the best we can as an advisory group.”

“We do not make the laws, nor do we control the judiciary, nor do we control the Executive Branch,” Musk elaborated. “We are simply advisors. In that context, we are doing very well. We cannot take action beyond that because we are not some sort of imperial dictator of the government. There are three branches of government that are, to some degree, opposed to that level of cost savings.”

The Trump administration has claimed DOGE has saved taxpayers $160 billion so far. Critics, including some on the right, said DOGE hasn’t achieved that level of savings. So, who is right? And how can the average person see the data and decide for themselves?

At Open the Books we take these questions seriously and have tried to bring some transparency to the question in the analysis below. We’ve also tried to develop an intellectually honest approach using two common sense standards.

The Durable Standard

A truism in politics is that there is no such thing as a permanent victory or defeat. Opinions and sentiments change and so do our political parties, majorities and laws. A program that seems permanent today may be gone tomorrow. Asking if a cut is “true or false” doesn’t tell the public much about whether a cut is, in fact, real. The right question is to ask: Is it durable?

Describing something as “durable” does not mean it is permanent or irreversible; it simply means it is hard to reverse. Durability is a spectrum or scale that measures how hard it is to undo something.

The most durable budget cut in our constitutional system would be passed by Congress, signed into law by the president and be clearly constitutional, or unassailable in a court challenge. Budget cuts become less durable when they lack any of these three elements.

For instance, President Biden’s executive order to forgive student loans was not a durable policy because he was acting unilaterally. Congress passed no law forgiving student loan debt and the courts struck down the action as illegal. Similarly, DOGE’s unilateral actions to cancel grants and contracts and fire personnel, along with some of President Trump’s executive orders, are not as durable as congressional actions – even if the savings targets are desirable and legally defensible. Case in point: President Trump’s executive order eliminating the Department of Education may, in fact, pass legal muster because the department itself has no constitutional basis, but a more durable cut would be to persuade Congress to eliminate the department through a bill the president could sign into law. Without that, the change remains vulnerable to challenge in court or simple reversal by a future president.

The Duty Standard

Similarly, just as “durability” is a spectrum or scale, so is the issue of duty or responsibility when it comes to measuring DOGE’s level of success or failure. Musk insists DOGE is an advisory group without dictatorial powers. It is not DOGE’s job to cut spending per se. Musk is right. Still, at a minimum, DOGE’s recommendations are a signal of the president’s possible intent to use his constitutional veto power to reject congressional legislation that rejects his recommendations.

Yet, a common refrain from DOGE’s congressional critics has been, “Cutting spending isn’t your job!” combined with “You’ve failed at your job!”

Huh?

Congressional critics want it both ways because they have failed at their own jobs for decades. We already have a permanent standing deficit commission. It’s called Congress. If members of Congress don’t like DOGE’s menu of cuts, they have every opportunity to offer cuts of their own.

In our constitutional system, the founders gave the job of budget savings to three branches but primarily to Congress. DOGE’s job is to identify, not enact, savings targets. It’s up to Congress to do the heavy lifting. And We the People have a responsibility to be informed and hold our elected officials accountable.

A Closer Look at DOGE Savings Claims

Because taxpayers don’t have access to real-time transparency and a real-time look at the Treasury Payment System, it’s still too difficult for even a highly motivated Joe Taxpayer to confirm the savings claims DOGE is making. It’s also far too easy for critics to sew doubt and confusion.

Open the Books auditors mined the data published on DOGE.gov – cancelled grants and contracts that make up the bulk of claimed savings – and found fewer than half of them could be confirmed with a simple review of public records. Joe Taxpayer could likely verify just 42% of contracts and 27% of grants with a simple review of the records.

Again, this doesn’t mean these targets aren’t real, it simply means it’s very hard for taxpayers who want to see additional savings to find proof and evidence of savings.

To its credit, DOGE and Musk have repeatedly said they would make mistakes and would take action to correct mistakes. Our review, we’re sure, is far from comprehensive or perfect either. Our work, and DOGE’s work, reveals the enormity and complexity of a task that can be made far easier with more transparency.

We believe normal taxpayers, not data scientists or professional auditors, need to be able to see the waste for themselves – and verify that DOGE is saving them cash. It’s critical to maintain public trust in the project and ensure demand for more efficiency persists for years to come. DOGE shouldn’t be a temporary program or a cultural flashpoint, but a movement that is always perfecting the American experiment and shifting power from the government back to people.

GRANTMAKING

The DOGE website listed 9,521 federal grants that they claim generated savings on behalf of taxpayers – either from cancelling them before they got off the ground, or more commonly by halting them midstream. But only 2,643 of those had claimed savings that the average American taxpayer could easily review and verify. That’s just a 26.76% success rate.

Most claims include a link to the details of the grant at USASpending.gov. There, taxpayers can read a description of the project the grant is funding, see which federal agency is paying, how much the federal government originally promised to pay (this is called the Total Obligation) and how much it’s already spent (this is called the Total Outlay).

In cases where the savings can’t be easily verified, a few similar discrepancies repeat themselves again and again. The first and most frequent category is a lag between real-time spending and public reporting. Congress and the administration can work together to close that gap.

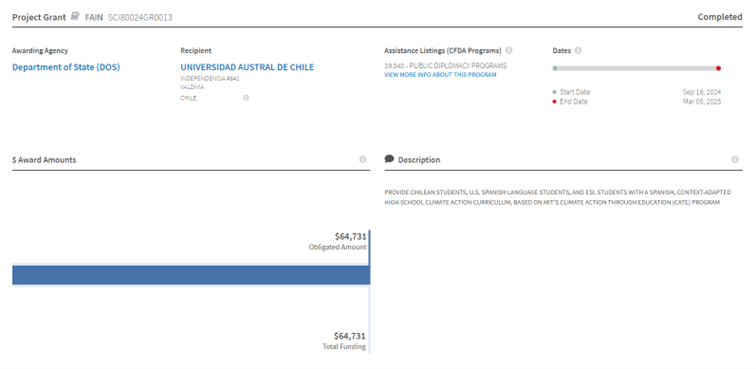

Take for example, this grant from the State Department to a university in Chile, Universidad Austral de Chile. The purpose is to provide Spanish-language, “context-adapted” “climate action curriculum.” The source material is MIT’s “Climate Action Through Education (CAFÉ) Program.

DOGE.gov values the contract at $64,731 and claims it saved $32,366. But when reviewing the public record at USASpending.gov, taxpayers can only see that the State Department did indeed “obligate,” or commit to spend, the $64,731 in its budget. But there’s no corresponding outlay. Presumably, half the money was spent since the last time the website was updated and since DOGE says they stopped funding the grant.

This is happening because USASpending.gov is limited to post-facto reporting. Taxpayers are looking at what agencies did in previous fiscal quarters. They submit their quarterly reports which are reviewed and posted another 45 days later.

But we’re flying blind when it comes to real-time – or just more recent – spending. DOGE employees, by contrast, are working inside the government and have access to payment information through the Treasury that Joe Taxpayer does not.

In other cases, not only do outlays lag behind real time, but the total obligation from the government does not match what DOGE says the grant is worth.

Take this example, in which the Department of Defense gave a scientific research grant to the University of Wisconsin. DOGE data says the total value of the grant is $2,103,513 and that they saved taxpayers $409,016. But at the link to USASpending.gov they provided, it says the Pentagon only obligated $1,705,000 and $443,348.25. That theoretically leaves more like $1.62M left as potential savings (or less if DOD already spent more money since its last public report was posted).

So, not only is the actual spending (outlay) potentially lagging behind real time, but DOGE and USASpending.gov (via a DOD report) disagree on the original costs.

That could theoretically be explained if the Pentagon were planning to obligate more money in future years, but the grant’s end date is already in the past (Feb. 28, 2025).

Another example is a good deal sillier, but illustrates the same kind of double-discrepancy. The State Department was granting money to a Slovenian cultural organization to send U.S. musicians, including a band called Never Come Down, on a tour of the Balkans! DOGE say the total value of the grant is $15,500 and they saved just under half of it, $7,500. USASpending.gov, however, shows just $11,079 obligated, and none yet spent. So again, we can’t confirm any savings at all, perhaps because of lagging reporting, but there’s also confusion about how much taxpayers were on the hook for in the first place.

Another discrepancy in the DOGE data set are savings claims and grant values that dramatically eclipse the actual obligations and outlays listed at USASpending.gov.

Take for example a grant from the now-infamous Agency for International Development (USAID). DOGE data says it’s valued at $50,000,000 and that they saved taxpayers $47,788,401. The link to USASpending.gov shows a grant to Johns Hopkins University for a vague endeavor to institutionalize equitable “knowledge management” that improves global health and development outcomes. Setting aside that this description is virtually unintelligible to laypeople, the website shows USAID obligated just $2,211,599 and shows nothing yet outlaid.

Why such an enormous difference? It takes further digging through the codes attached to the grant to find out that this grant is part of a larger project, “Foreign Assistance for Programs Overseas,” which makes up a much bigger chunk of USAID spending. Given that the agency was largely dismantled and moved under the control of Secretary of State Marco Rubio, it seems plausible to look elsewhere.

But even checking the project’s unique identification number in the CFDA (Catalog of Foreign Domestic Assistance), fails to add clarity. SAM.gov, run by the General Services Administration, shows the total projected cost of the project was estimated at $32M as of Fiscal Year 2024. That still doesn’t match the $50M value listed by DOGE or some $47M in claimed savings. Were they projecting hypothetical costs and savings further into the future?

Whatever the explanation may be, it’s clear that these kinds of discrepancies can’t be quickly ironed out by taxpayers who have their own busy lives to attend to. At this scale, with tens of thousands of hyperlinks to review, it would take a team of public data experts instead.

In rare instances, USASpending.gov showed spending that directly disproved a savings claim from DOGE. For example, a State Department grant to an entity in Beirut has its purposes masked for security reasons. USASpending.gov shows $34,167 obligated – the same as the value listed by DOGE.gov. But while DOGE claims the full amount as savings, USASpending.gov shows $14,703 was already outlaid.

In a few other instances, DOGE’s claims appear too modest, again likely due to lag times in reporting. For example, DOGE and USASpending.gov agree this grant from the EPA is worth $4,000,000. DOGE claims $2,467,892 in savings, but USASpending.gov reflects there’s $2,976,892 left in potential savings. It’s likely the half-million dollars was spent more recently, after the last update was loaded into USASpending.gov.

The final type of discrepancy is well, less a discrepancy than a blind spot. The information is simply not available to taxpayers. A portion of the grants identified by DOGE have details that are redacted for national security reasons. That’s frequently the case with foreign funding meant to spread Western culture and democratic values, but which foreign regimes could view as hostile acts.

CONTRACT SPENDING

Another key way the government spends discretionary funds is by contracting with third parties, both public and private.

Unlike USASPending.gov, where all the grant reports are located, the savings claims for contracts are backed up by records in the Federal Procurement Data System (FDPS.gov). This database has a much more complex and exhaustive set of data points, from spending figures, to contract status, points of contact, benchmark dates, and more. There’s even a field labeled “Initiative,” where federal employees can associate the contract with a directive from the White House.

But here, too, there were problems doing a simple spot check of the DOGE claims.

The data that Open the Books pulled from DOGE.gov shows 8,221 contracts were identified for savings. The attempt to match DOGE’s claimed savings with public spending records went a bit better, if not a smashing success. 3,476 of the contracts showed the government had stopped obligating funds before they’d maxed out the contract, and that the figure matched the savings claimed by DOGE. That gave us a match rate of 42.28%.

In many instances, it was actually quite simple to confirm the savings. For example, a whole tranche of contracts that cut across various federal agencies were marked “TERMINATED,” of them bearing the descriptor “DEIA Training” and many of them claiming the full value of the contracts as savings. It’s easy to intuit that DEIA (Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Accessibility) training would get the axe for being at loggerheads with President Trump’s executive orders directing Cabinet secretaries to rid their departments of divisive DEI ideology.

One such contract between the USDA and AMA Consulting LLC was worth $25,000,000 and every penny was claimed by DOGE as taxpayer savings. Another, between the Treasury Department and Inroads Inc. was worth $6,500,000 – again, all of it was saved.

Then came the discrepancies.

Even in the DEIA Training category, which seemed straightforward, there are contracts like this one: a Treasury contract with the Washington Center for Internships and Academic Seminars that DOGE values at $88,734. Federal Procurement Data System (FPDS) records show that’s indeed the total contract value, but it also says that full amount was obligated for spending. More inexplicably, DOGE lists as savings just a dash mark “-“.

If there were no savings, why is it listed among the contract savings by DOGE? Did DOGE somehow claw back obligated monies, and did it happen more recently than the last update to FPDS.gov? The data quickly becomes inscrutable and requires further explanation from DOGE or government employees in the relevant agency.

Another category of discrepancies closely mirrors what auditors found among the grantmaking claims. Neither the total value of the contract nor the purported savings listed by DOGE match numbers found on FPDS.gov.

For example, the Department of Defense had a contract with a company called Securigance for “network support services.” DOGE values it at $1,011,505,945 and says taxpayers saved $565,707,257. But according to FPDS.gov, $1,241,383,322.58 and the total obligated to be spent was $419,991,426.77. If those numbers are accurate and up-to-date, that means the savings would be more like 821,391,895.81, a quarter of a billion dollars more than DOGE takes credit for saving. But in either case, DOGE and FDPS seem to disagree on the total value of the contract in question, with no easy recourse for the inquisitive taxpayer.

Other contracts that would be confusing for taxpayers to sort out are listed as IDV (Indefinite Delivery Vehicle). This type of contract allows the government to sign a contract for a certain value, but pay for goods or services over time and negotiate those costs separately per instance.

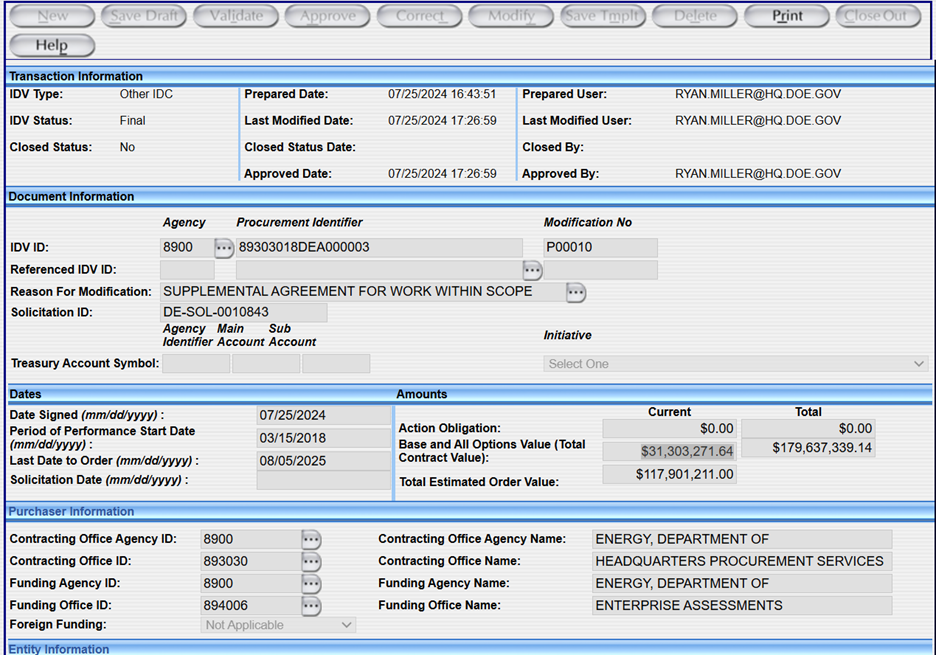

For example, this contract between the Department of Energy and Kumono Government Services, LLC is for security and safety trainings at the DOE’s National Training Center in Albuquerque. Both DOGE and the FPDS roughly agree on the contract value. DOGE has it at $179,000,000 even, which FPDS says the total contract value is $179,637,339.14.

DOGE says they saved taxpayers $15,652,636.00 on this contract. But the FPDS shows a smaller current contract value of $31,303,271.64. It also reflects a total order value, presumably money already spent, of $117,901,211. Regardless of how one parses those numbers, it’s impossible to verify the $15.6M of savings.

In rarer instances, some contracts are simply listed as “Not found in FPDS.” Oops, we lost the records.

In a few other cases, contracts are unreported because their total value is less than $25,000 and escapes transparency requirements. The government calls this a mere “micro purchase,” but most taxpayers would more readily describe spending $25,000 as a significant life decision.

Then there are the truly confounding. Take this contract between the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Rose Li & Associates Inc. DOGE values it at $1,817,552.00 and claims $1,031,379.00 in savings. But on FPDS.gov, the total contract value is listed at just $820,024.44. Of that, the whole amount is obligated – committed to be spent. Then, in the “current” column for the most recent quarter, there’s a negative amount listed, -$766,561.51.

Did DOGE pull back most of the obligated funds in the same quarter they’d been spent? And why don’t the total contract values match in the first place. There’s no obvious way for taxpayers to mix these numbers and find the savings amount DOGE claims.

Again, like the data on grants, there are a significant number of contracts that DOGE lists as “not available for legal reasons.” For the most part, this is again an understandable consequence of protecting national secrets -- and it’s reflected in the large proportion of contracts redacted by the Pentagon or whose descriptions are masked by the State Department specifically.

The Unfinished Business of Real-time Transparency

Led by Musk, DOGE has publicized extraordinary problems with our federal spending – not just silly waste, but structural challenges with data systems and recordkeeping that prolong the waste. They’ve sent a clear signal to Congress: it’s time to get serious about cutting waste.

But reaching the Durability & Duty Standards starts with transparency. A steady stream of examples that taxpayers can trust and verify will maintain a persistent demand for Congressional action.

In too many cases, a normal American who’s not a data professional cannot simply take a look at these records and confirm the savings DOGE has claimed.

To be sure, and as we’ve noted, DOGE has done extraordinary work under Musk. And by no means do all of these discrepancies fall solely at the door of its offices; data portals are only as good and as up-to-date as the upstream reporting they receive.

But as long as a transparency gap remains, a trust gap remains to be exploited.

When it comes to the DOGE.gov savings claims, there’s one clear remedy: opening “America’s Checkbook.”

In all but the truest of national security exceptions, taxpayers should have the ability to track spending in real time – right along with DOGE and the government employees they’re meant to hold accountable for success. So let’s let taxpayers have access to a modified version of the same Treasury Payment System that DOGE and Treasury officials can see.

While it was the subject of heated controversy when Musk tried to access it, that never should have been the case. Why on Earth would the President and his chosen aides and Cabinet officials be barred from seeing how the government they run is spending our funds? Just as importantly, this money belongs to the Americans who earned it and then contributed it to the federal government in exchange for efficient, effective public service. Taxpayers should be able to see payments coming and going just as they can in their own bank accounts. After all, it’s their money.

METHODOLOGY NOTES

*Findings are based on data pulled from DOGE.gov on April 29, 2025. Data will change as reporting is updated in the system.

For contracts, Open the Books checked the savings by reviewing the FPDS website for the total value of the base contract and all options, and checking that figure against what the feds had listed as a “total action obligation” – the amount it committed to spend.

For grants, Open the Books checked USASpending.gov entries, calculating the difference between the obligated and outlaid spending totals. They matched that figure with savings claims made on DOGE.gov.

99% of congress is the best government money can buy.

TERM LIMITS.

America has a SPENDING problem, NOT a taxing problem.